Read All About It

Newspaper articles about Ruskin Pottery and the Taylors

“I Remember.”

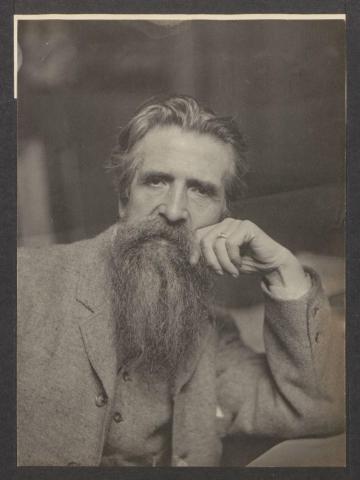

Art Developments in the Midlands By Mr Edward R. Taylor, A.R.C.A.

Fifty odd years ago I entered upon my chosen vocation by becoming the first student in the old School of Art at Burslem- a fact which I recalled two months ago in a connection with the opening of the new Wedgwood School of Art. The Burslem School was in those days held in a low room, about the size of an ordinary dining-room, situate in the yard of the Legs of Man Inn, and the late Mr. J. Muckley, an old Birmingham student, was the art master. Burslem wore in my early rememberance a very aspect to that which it presents to-day. It was a comely town, with green fields and pleasant gardens within a “few minutes” walk from any part of it, and there was a beautiful stretch of country between Goldenhill and Lane End and between, Hanley and Silverdale. From the Burslem school, I passed on as a student in training at South Kensington, I have a memory of seeing both the Great Exhibition of 1851 and that of 1852. Of the former what I most visibly remember was the glass fountain made by Messrs, Osler and that forest trees were inside a building, and by ascending to the galleries one could get among the upper branches with the sparrows flying about. At the latter, among other work, I made a water colour drawing of Messrs. Hardman’s exhibit of ecclesiastical metalwork of Waring’s “Art Treasures”. In the latter year I obtained the appointment of headmaster of the newly provided School of Art at Lincoln, and at the beautiful cathedral city in the Fens I remained for thirteen years or so.

When I went to Lincoln I thought of being an art teacher only, but a mere incident led me to work of a more individual nature. The honorary secretary of the Art School was a cathedral canon, and also an amateur painter. I was out with him one day when I happened to notice a fine old man, and at once exclaimed that I should like to paint him. “Well,” said the canon, “he is one of my parishioners and I’ll get him to sit for you.” I finished the picture and when May came round I sent it to the Royal Academy direct, instead of to a packing agent. In those days no notice was sent out to exhibitors as to whether they had secured a place or not, and a fortnight passed before I ventured to send for a catalogue. Imagine my delight to find that the picture was “in” and not only accepted but well(*) hung. How long ago this was may be realised when I mention that this was in the day of the old rooms now occupied by the National Gallery. In the following year a portrait of my mother, entitled “Knitting,” also found place on the Royal Academy walls.

At Burlington House

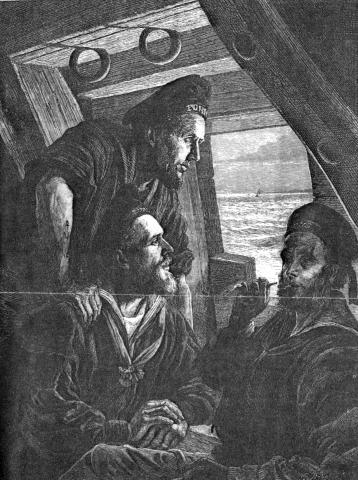

On removing to Burlington House, the Royal Academy attempted to secure the better hanging of pictures by not overcrowding, and this first year in the new rooms I had a large picture on the line with plenty of wall space all around it; but the overcrowding soon began again. I think artists would prefer that their pictures should not be hing tha badly hung. Other pictures which I have exhibited at the Royal Academy were “Nearing Home.” a life-size picture of sailors looking out of the porthole of a man-of-war, which was engraved in “The Graphic,” with an extract from a very favourable Press notice of the picture by W.M Rossetti; “The Cloister Well,” a large picture of Lincoln Cathedral; “Twas a Famous Victory,” painted in the Midland Institute from a few hours sketch in the National Gallery, the caretaker of the Institute sitting for the veteran; and several landscapes. While sculpture has greatly improved, painting is, with one or two notable exceptions, in an ebb tide as compared with the sixties, when an Academy exhibition would contain several pictures by Millais, and pictures by Watts, Mason, Walker, Hook, Whistler, Orchardson, Linnell, Alma Tadema, and others of high standing, while outside was the work of Holman Hunt, Ford Madox Brown, Rossetti, and Burne-Jones.

While at Lincoln I remember Chancellor Benson relating a story of how the only art education he received was from the famous headmaster of King Edward’s School in Birmingham, Dr. Prince Lee, who told him to go to the Round room of the School of Art, now the Royal Society of Artists, and to gaze at the bust of Venus de Milo for half an hour. The only evening students at Lincoln were people mainly engaged in agricultural implement-making, and they took to art as well as to geometry and machine drawing.

My subsequent associations with art work in Birmingham had quite an accidental beginning. I was in those early days a member of the Hogarth Club and while there was one evening Wilmot Pilsbury, the well-known member of the Royal Water-Colour Society, himself a Birmingham man, asked if I was not going in for the art headmastership in Birmingham, which had been vacant for a year, but of which I had not heard. I did so and received the appointment in 1876. On my way back from Birmingham to take up my new work in what was, I think, the oldest school of art in the country I never suspected but that the school was accommodated in a good building. Instead I found it housed in the top room of the old Midland Institute. To reach it was an awful climb up four or five flights of stairs, and the place itself was ill-lighted. I told the late John Henry Chamberlain, who was then chairman, that we must get a new school, but his reply was that so little was the interest locally taken in art education that we should not get five pounds towards the cost of providing a new school. Then there came a period of enlargements at the Institute, and the School of Art, being something of a Cinderella in those days, we had to make the best of temporary quarters in the top rooms of the Council House, and even about the corridors.

The School of Art

When we went back to Institute we had little more room, and the place as still dreadfully crowded and inadequate. Then I met by appointment the late Sir Richard Tangye at a memorable conversazione of the Royal Society of Artists, and had a long conversation with him. All my friends thought that I was selling him pictures, but we were discussing something of much more importance. He asked me at the time not to mention anything of what he had said, as he and his brother, Mr George Tangye, promised first to do something for the Art Gallery. It was sometime later when Sir Richard announced his proposals relative to the School of Art. Thus came about the building of the present school, or, at any rate, the first portion comprising the south and front, Mr Cregoe Colmore giving the land. Mr John Henry Chamberlain, the then chairman, estimated that there was nine times more space than was provided in the old building, but progress was made nevertheless. The number of students increased, additions to the Art School had to be made, and the rest is the story of the continued and gratifying success of the Birmingham School of Art. Among its early students, as everybody knows, were Walter Langley and W.F. Wainwright, and many others who have since obtained distinction.

When I had reached the age of sixty-five my time for retirement came, and the last day of my head mastership, with all its happy surprises and warmth of good wishes from masters and students, is among the best of my memories…

Since my retirement I have acted as art examiner for South Kensington, one of my colleagues being the veteran pre-Raphaelite painters, Arthur Hughes, bright and competent as ever; the Society of Art Masters, of which I was, by the way the first chairman; and the Central Welsh Board; and for the Cambridge Locals. I was also the art and technological expert, in conjunction with Mr. Llewellyn Smith as general expert, engaged on the draft of the London County Council scheme for art education, and in that connection I have visited nearly all the art institutions, technical, and many of the secondary, and elementary schools of the Metropolis. In my later days I have turned, with my son, attention to the making of The Ruskin pottery. My father was an earthenware manufacturer at Hanley, and in my youth, therefore, I had seen something of the potter’s craft. The Hanley productions were plain white ware exported largely to the United States. In developing this Ruskin pottery the commercial conditions, so much worse than fifty years ago, were the principal difficulty. The shapes are all made on the potter’s wheel, all decorated by hand, and the painting is all in and under the glaze except the lustre, while only leadless glazes are used.