Howson Taylor Master Potter

A Memoir with an appreciation of Ruskin Pottery

By L.B. POWELL

City of Birmingham School of Printing

Central School of Arts & Crafts

Margaret Street

1936

FOREWORD BY THOMAS BIRKETT

To all who appreciate fine craftsmanship, this little book is dedicated. William Howson Taylor was a great craftsman; his medium was the potter’s clay, and the glazes applied to it: his tools were the potter’s wheel and the firing kiln. With these he produced some of the finest pottery the world has seen: fine in shape and colour; some rich, some delicate, some subtle. Therefore he should not lightly be forgotten

William Howson Taylor is dead: his works will be joy to future generations, and it is the purpose of these pages to put upon record such facts as can be ascertained of the history of the pottery, which in 37 years, from 1898 to 1935, became world famous; so that the collector of the future may know something of the circumstances which attended its production. Like all honest craftsmen, he was man of great simplicity, shy and modest, with a very lovable character; inarticulate about his work but a cheerful companion, loved and admired by all his work people and all who came into personal relationship with him. But there was no false modesty: he had full knowledge that he was producing good work and was proud of it.

In July, 1935, the pottery was finally closed and Mr. Taylor and his wife went to live in a cottage at Tuckenhay, near Totnes, South Devon. It was hoped to enjoy many years of well earned retirement practising his one other hobby- gardening. He had been unwell for some time and died in a local hospital on Sunday evening, September 22nd, 1935, and was buried in the churchyard of Ashprington.

To assist the collector, all the known ‘marks’ used by Taylor are reproduced. Some pieces were left entirely unmarked.

Thanks are due to Mrs. Howson Taylor, and the Misses Taylor, his sisters, for much useful Information about Mr. Howson Taylor; to Mr. H. Percy Marshall, the Borough Librarian of Smethwick, for reading the proof; to the Sun Engraving Co. Ltd., Watford, for the colour blocks used in the illustration; and to Mr. Leonard Jay, Head of the Birmingham School of Printing, for his generous helpfulness.

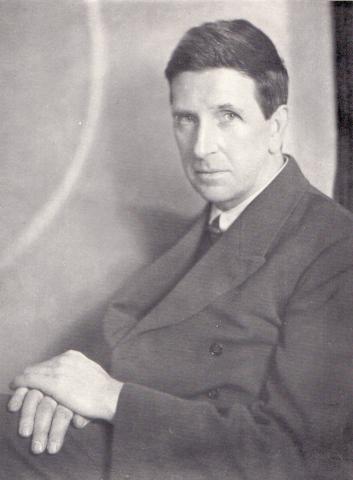

HOWSON TAYLOR MASTER POTTER 1876-1935

Ceramic art provides one of the most outstanding examples in the whole realm of artistic activity where the application of aesthetic sense elevates things of common use to the point of enshrining, for its own sake, the appeal of beauty. And its beauty comes surprisingly, if for moment we can think of the matter primitively. For what can seem less likely to possess beauty enduringly than pot, the very name of which, brief, and blunt, wholly lacks grace? Yet what is lovelier when clay, meanest of earth’s substances, has known the cunning of an artist’s hand, an alchemy of mind as well as of the furnace? Shakespeare, seeking analogy for loss of spotless reputation, turned to ‘gilded loam and painted clay.’ Yet muddy reputation bears no comparison with the well-finished product of the potter’s art: Shakespeare was thinking of the baseness of the material, and base enough it is, lowly enough in place and estimation, until metamorphosed by the artistic spirit.

It is probably the oldest of the arts: can be looked upon as having given primitive man, who sought and moulded the clay of alluvial plains and river beds, his earliest impulse towards the intelligent appreciation of form, this form being something apart from the creations of nature’s own inexhaustible invention. When to form was added colour, and to colour the subtleties of glazing, fine pottery came to be numbered among the prized possessions of men, and has so remained, for thousands of years.

It has a background historically, and in sociological interest as well as aesthetic value, as fascinating as that of any other art, and one just as changeful. In the old dynasties and autocracies of the East, the master potter enjoyed Royal indulgence which went to the length of ensuring complete freedom from economic uncertainty; in the new democracies of the West (the few that are left), he struggles to make a desperate living by his art. But the love of fine pottery persists. It survives ages of degeneracy in artistic taste because it is not an exclusive art—is indeed anything but esoteric in appeal; and because the desire to see beauty of form and loveliness of colour, even in the common objects that surround us, is the expression of a human need which will not be extinguished easily. Those who are wise, therefore, are grateful when a master potter rises in their midst whose approach to the art has the same insight and is similar in technical skill when compared with that of the illustrious potters of the ancient world.

Such a man was William Howson Taylor, and the fact is reason enough for the production of this small volume, which seeks to record while the memory of him is fresh an career, and an appreciation of Ruskin pottery, made under estimate of his qualities as an artist, a brief outline of his the ceaseless inspiration of his skill, which has enriched public and private collections everywhere.

Heredity took a larger share in the shaping of Howson Taylor’s career than is the case with many artist-craftsmen. The potter’s furnace looms like a symbol of destiny in the background of his family history for generations. His father, Edward Richard, a former head of Birmingham Central School of Art, was a native of Hanley and came of a long line of potters. Born in 1876, William Howson grew up from infancy with the feel of the potter’s clay known to his hands, the love of form instinctive in his heart, and the fascination of colour ever present to him. But he knew the early sharpness of economic necessity which fate seems to decree shall be the lot of most artists labouring to give new beauty to the world and nothing less than this was the aim of father and son, for both were wholly uncommercial, and sensitive only to art. Three years of experimenting on his own account with clays and glazes and colours had seen Edward Taylor’s savings diminish almost to vanishing point, for the hobby was an expensive one: and Howson was in his middle twenties, eager for a potter’s career, when his father called together the family (three daughters and two sons), acquainted them with the slenderness of his resources, and sought their advice whether to stop or go on. Unanimously they agreed to go on, and Howson Taylor must have rejoiced that the enthusiasm of his schooldays (he had spent his youthful leisure experimenting with a kiln at home) was not prematurely to be extinguished.

For a few more years, Edward Taylor, with the assistance of his son, struggled against the obstinate refusal of the world to admit the excellence of his pottery. At length the tide turned. The pottery gained a notable award at an International Exhibition at St. Louis in 1904. It won great distinction two years later in Milan, where it had to contend with the best modern ceramic art of Italy. It was then that a Japanese expert affirmed Ruskin pottery to be worthy of comparison with the finest of the Ming period. London’s recognition came at an exhibition in 1908, and Brussels, in 1910, added one more to these early distinctions.

In 1912 Edward Richard Taylor died. He had lived long enough to see his pottery acknowledged in important places and by important people: had seen in the son, who now assumed complete control of the business, the awakening of a genius which was to place Ruskin pottery yet more securely among the finest pottery of any time.

During the ensuing years many thousands of pieces were sent to America at rising prices. A firm place was found even in the markets of the Far East. One by one the European galleries, and others elsewhere, acquired specimens, and there are now few important galleries where the products of the little factory at Smethwick are not represented. Royal families, including our own, purchased examples for their own collections.

With these bright auspices attending it, the manufacture of Ruskin pottery for a few years enjoyed financial success. Then came the Great War, and with it neglect of the arts which persisted, with occasional signs of recovery, throughout the post-war years. Thenceforward the tale of Ruskin pottery, in the purely commercial sense, is briefly told.

For some years, though its beauty and variety continually increased under the influence of Howson Taylor’s fertile skill, the undertaking existed on a falling turnover. Eventually he faced a prospect bitter for any man wedded to art—the need for commercialising his production by turning out inexpensive examples which in this case would be cast in moulds instead of thrown on the potter’s wheel. This he did in a final attempt to keep his workers together, but it met with only temporary success. In 1934 Mr. Taylor accepted what he then regarded as almost inevitable, and decided to close the factory and discharge the people with whom he had been one since earliest days, working among them with his own hands, supervising their efforts with the closest personal attention, imparting to them his own enthusiasm. For the better part of a lifetime his imagina tion had been spent in evolving form from formless clay, giving it an exquisite beauty, rivalling in its surface treat ment the lustre of gems and embodying rich or subtle harmonies of colour inspired, very often, by the variety to be found in nature, as in the wonders of mingled colour in shallow rocky pools left by receding tides, or in the bloom wrought by sunshine and gentle airs on a fully ripened peach.

For 35 years Howson Taylor lived for his pottery, and took not a single long holiday, but spent many of his Saturday afternoons in the country in the company of his workers, finding vastly more in common than is usual between employer and employed. His story is one of single minded devotion to an art rare in modern days. In spirit he belonged more to medieval times than to the twentieth century. Modest to a degree which sometimes daunted his friends for he would rarely speak and rarely wrote of his craft-his retiring disposition kept his name in the background while the fame of the ware he produced grew everywhere. To meet and converse with him was to be dissolved one gained the conviction that he was a man in conscious of immense reserve, but when his diffidence was whom the ceramic art had been a sustained—and sustaining-passion, and whose completeness of expression in it was preordained. In humility and gentleness of mind, in the excellence of his skill and wholehearted absorption in it, he was a modern Fra Angelico, translating his gifts into clay.

In the period—roughly a year—which followed the announcement of the closing of the factory, Howson Taylor coloured, glazed and fired a large number of pieces remaining in stock in biscuit form—i.e., the clay having undergone its first process of baking. It is no secret among those who knew him well that in this valedictory period some of the finest of his work was produced, and it was characteristic of him that, freed finally of all commercial considerations, he should devote to these pieces a more intensive degree of skill than ever before. He had, on his own confession, never worked for financial profit. His driving force had been from youth onwards the artistic impulse born in him. That impulse had come to him from ancestors whose lives had been spent in the Five Towns, but its roots ran far deeper, penetrating, indeed, almost as deeply into the past as the art of pottery itself. Probably no modern potter knew more than he the ancient processes of his craft. He was near to the masters of the past alike in mental approach and technical method. He stood at the end of a long line of potters, direct in descent, and was the epitome of all they knew, exceeding them in the excellence of his skill, the depth of his knowledge, and the prescience with which he could assimilate and exemplify the oldest traditions of the art. It has been said that his ‘secrets’ died with him, and it is true that, before his retirement in 1935, he did destroy with his own hands many papers relating to technical matters such as body mixtures and glazes. But to speak of jealously guarded formulae and to regard the matter as being one of rule and precedent, all of which could be set down on paper, is to under-estimate sadly the personal inspiration and skill of the potter’s craft. His mastery over material is no less a personal art than that of the painter and sculptor, and what died with Howson Taylor was that which dies with every artist – dies with him, but lives on in his work.

We cannot consider the qualities which give Ruskin ware its assured place among the finest pottery of any time without also considering what the essential characteristics are which give pottery its validity as an art-form. Like every other art, it possesses qualities, inherent in its nature, the complete realisation of which gives perfection. But it is also, again like every other art, amenable to other qualities, not essen tial to its nature, which are borrowed for the sake of the adornment they are considered to yield. All the arts are addicted to this borrowing from each other: in periods of artistic decadence the borrowing is widespread and inten sive, a habit which becomes a vice, tending to obscure the real nature of the art concerned, until it may become diffi cult to perceive what are the authentic qualities of any given form of art. In England, for example, the anecdotal pictures of Victorian painters deadened perception of the intrinsic qualities of painting as an expression of the aesthetic spirit. Music, when descriptive,’ is less than itself, sculpture is weakened by the extent to which its purpose is conceived as the literal representation of the human form.

We can, of course, admire such technical skill as may be exhibited in an art-form in which the borrowing has been great, but unless the right of form to exist independently in its own free world be recognised, the re-assertion of that right is bound to seem strange, ill-mannered, perverse;

and will evoke vague sensations of unrest in us.

Pottery, as much as music, sculpture, and painting, possesses its own exclusive nature of appeal. If it does frequently go to external sources for inspiration, this in spiration is not concerned with the fundamental quality of pottery, which is form. Within the world of form the artist is free imaginatively, and restricted literally only by the nature of his medium, and the purpose the result may be expected to serve.

Colour obviously ranks next to form, and must be considered as a primary quality. Glazing, and other methods of surface treatment, linear and plastic forms of decoration, are secondary considerations, like musical variations adorning a main theme. Pottery is therefore like sculpture, obeying the same necessity for an aesthetic evolution of form, and as with sculpture, pottery has to be thought of, and mentally felt ‘in the round,’ as thing existing in space and presenting a similar artistic appeal from whatever angle it is regarded. It is near paint ing when the use of colour is decorative, and when these two qualities, aesthetic form and decorative colour, are combined aptly, pottery attains its highest degree of ex pression, becomes a work of art, yielding an extraordinary feeling of calmness and repose. And unlike all other arts, it tempts the sense of touch as an exercise of the aesthetic spirit. Thus when we see a finely made example of the potter’s art, we feel impelled not only to enjoy the appeal of its colour, but to handle it as well, to let our fingers run over its surface, to appreciate by touch its volume and shape, its lightness or perhaps its weight. In so doing we experience an extension of the purely mental apprecia tion of the beauty of form, and are near, if indeed we are not actually exercising in a slighter degree, the primitive impulse, the source of aesthetic emotion, which in pottery been known to men irrespective of race or climate. For has been a sustained passion through the ages, and has thousands of years the Chinese have believed that constant loving handling and contemplation of their little carvings inspire us too when we have in our hands a beautiful piece of ceramic art. This blending of the physical with the of jade brought suavity and composure to the owner and kept depravity from the heart, and such a feeling may intellectual appreciation is worth pondering.

Walter Pater was right when suggesting that the touchstone of value in art is sensation, but the sensation is fuller and likely to yield deeper rhythmic significance, when visual awareness is heightened by the sense of touch.

The impulse which inspired Howson Taylor in his Smethwick factory was one and the same with that which stirred men who made their bronzes and pottery in the valleys of the Yangtze and the Yellow River ages before the Christian era began. Neither in method nor in spirit did he differ from the potters of ancient times in Old Cairo, Alexandria, Damascus. He was a great potter because of this identity of spirit with them.

But if pottery is like sculpture in one thing, near paint ing in another, we shall see how it is freer than either in one important direction. Between the idea or the vision, and its complete realisation externally, the sculptor and the in the course of which the initial conception may be painter contend with the long physical labour of creation weakened. What the painter and the sculptor see and feel in a visionary sense may diminish in intensity as a driving force or disappear completely before the act is finished, unless he has the skill of genius to retain the impulse un impaired. But the potter sitting at his wheel, swiftly controlling with sensitive thumbs and fingertips and palms what was a minute ago an amorphous lump of clay, is in a better position than either, his artistic impulse grow ing, assuming reality as the material in his hands comes to shape. It may be said, with very near approximation to the truth, that thought and the form become one in his hands: his impulse springs swiftly to aesthetic life, gains at once in significance. In all art this sense of immediacy is inherent.

In Howson Taylor it was ever present, and is the quality of which we are aware, at first subtly perhaps, and then with increasing conviction, every time we regard the assembled examples of his art. It is the more remarkable that this should be so when we consider the fascinating variety of forms his pottery assumed. The variety indeed seemed endless, yet there were very few occasions in the whole of the great output from the Ruskin works when it could be said that the aesthetic conception of form, as thing pure and satisfying in itself, had been violated, or that instinct for the right thing was lacking. The fact offers impressive proof of the depth to which this master potter’s instincts were rooted in the past, and even when his wonderful achievements in colour and glazing are duly considered, I am disposed to think that this one quality, the directness with which artistic thought was realised in satisfying form, must remain the outstanding character istic in Howson Taylor’s art.

The glorious range of colours he achieved, the almost infinite subtleties of tone, the rich ness of glazes and variety of surface finishes, tend naturally to obscure this simple truth. These were the refinements of his art, and they called for an intensity of research, depth of insight, a patience and skill which have not been equalled in the ceramic art of our own time: but he was first and foremost a creator of form in thrown clay, excel ling in this before excelling in his command over the mysterious and captivating resources of high temperature firings. We cannot assess accurately his place among the great ceramists without first considering the sources of his inspiration to create pure form.

If we accept the view that art is a lowly but marvellous symbol of the cosmic order itself, it becomes easy to regard its humblest manifestations as having universal significance. The well-shaped vase, so well balanced that we cannot speak of its ‘proportions,’assumes as it were an eloquence as complete in its way as any expression of the sculptor’s art. Its maker has evolved order out of chaos, given meaning to shapeless clay. And dealing with such material, he works in a very wide field of ästhetic emotion and activity. Within it, he arrives at form by a process of mystical intuition. Confronted with the plasticity of clay and the equilibrium of the wheel on which it is thrown, he may build up a structure in perfect harmony with thought: and its form is the fruit of a rhythmic gesture, owing nothing to narrow naturalism, but possessing its own logic, from beginning to end. In such manner, it is clear, Howson Taylor worked.

With remarkably few exceptions, his shapes were in the artistic sense of the word powerful, possessed of a dynamic symmetry which was the result of vision and energy fused into one, and they gained elegance without any indulgence in ostentatious virtuosity. In this imaginative apprehension of form he was much nearer to the Oriental than the Hellenic spirit.

He had a breadth and power and restraint in form which may be compared worthily with the best examples of The Sung Dynasty, the classic age in China’s ceramic art. While the Greek potter, and even the Chinese potter during certain dynasties, were influenced by painting and metallurgy and resorted to archaic and naturalistic conceptions of form and decoration, this modern English potter expressed his artistic faith in pure form, and was content to leave to others the representational antics which have debased ceramic art at many times, and in many places. Nymphs and shepherdesses, character-groups and Toby jugs, made no appeal to his sense of the significant. These and many an allegorical fancy expressed in pottery had done for the art what the Georgian periwig and the Roman toga had done for eighteenth century English sculpture, and he left them severely alone.

If I have emphasised in the foregoing Howson Taylor’s claim to distinction as the creator of pottery fine in form, that has been because his success in the realm of colour was such that it might, in some minds, obscure his great sense of plastic values. In form he used the clay to demonstrate laws known with a certitude borne of the generations of potters preceeding him. In colour, by the nature of things, he was less guided by certainties of intuition, and was from first to last an experimentalist, seeking from natural substances the inspiration for his brilliant hues, the subtlety and richness of his harmonies of colour, and the depth of tone he so often achieved. He laboured to win for the fired clay some of the most beautiful of natural effects. The bloom of the peach has been mentioned, and it was characteristic of his zeal that he should seek, like the Chinese, to perpetuate so transient a charm, and succeeded with soft rose-coloured glazes, delicately flecked with the colour of peach, which permitted the fine underground to shine through.

But any general consideration of colour in Ruskin pottery must be preceeded by a brief outline of the materials and methods used, inevitably brief, for the melancholy reason that so little is known definitely, and we can only speculate upon the formula and processes by which some of his most wonderful results were achieved. In the earliest days of the kilns at Smethwick a local clay was used, from pit not many yards away, and it was characteristic of the farther than this for material. It was used at first princi founder of Ruskin works that, at first, he should go no pally for tiles. They were the humble beginnings of an art soon to enrich salons and Royal drawing rooms and private and public collections of ceramics everywhere. This local clay was soon found to be unsuitable for the finer work Howson Taylor longed to produce, and it was abandoned for a mixture in which the essential ingredients were ball clay and china clay, stone and calcined flint. These gave fine white body, which was used thereafter for all Ruskin products.

Lead, which had been used for so long in the coarser glazes of cheap pottery, was eschewed at the outset, and for the fine art productions of the factory no moulding, cast ing, or machine processes were employed in the potting, nor were printing, lithography or gilding used in the decoration. The latter was always hand-painted, or em bossed or impressed upon the clay. In short, the true artist’s respect for his material was a characteristic ever present, and contributed largely to the purity of form, the richness of glaze, the delicacy of tone or sheer joy of colour which are the outstanding qualities of Ruskin ware. And as the colours used were nearly always incorporated with the glaze, they were obtained in the main from the few oxides which offer the necessary degree of resistance to the great heat of the potter’s furnace.

Even so, we know that the of colour treatment and glazing.The first were the soufflé colour effects obtainable were almost unlimited. Broadly speaking, Ruskin ware is divided into three main groups wares, with or without hand-painted patterns, in which single dominant colour is present, varied often by mottlings, cloudings and gradations of tone. In this group the colours range from deep blues and greens to turquoise and apple-green, purple to mauve and warm pink, soft greys and celadons. Particularly beautiful is the celadon ware, which, in refinement of colour and elegance of form, offers evidence of the admiration the Smethwick potter felt for the work of the Chinese masters. The ware to which the name celadon is given existed in the T’ang period (A.D. 618-907) and became one of the glories of ceramic art during the Sung Dynasty (A.D. 960-1279). It may have been named after the Sultan Saladin(1138-1193); though a much later theory assigns the origin of the name to the green dress of the shepherd Céladon in D’Urfé’s pastoral play ‘L’Astrée’ of the early seventeenth century.

In the Ruskin soufflé group, many examples were decor ated with hand-painted patterns in one flat colour. If Howson Taylor’s career had been prolonged, it is reason ably certain that he would have turned again and again to the task of endeavouring to recapture the beautiful waxy surface quality, the bewitching colour-tone of green and the wide brown crackles of the Sung celadons such as were seen in the Chinese Art Exhibition at Burlington House.

The second group comprised a wide range of examples incorporating a new treatment of lustres, developed by much patient research, and yielding many beautiful decor ative effects. Colours in the lustres included lemon-yellow and orange, sometimes with an under-glaze pattern in green or bronze, delphinium blue and kingfisher blue, pinks, purples, turquoise, light and grey greens and browns, and in every case the lustres, like those of the best periods of ceramic art, served to enhance the distinctive pottery character of the form by giving it depth.

But exceptional though Howson Taylor’s achievements more he would still have been a great potter—the full were in these two groups and if he had done nothing In the soufflé and lustre groups, monochromes and colour glory of his art is not seen till we come to the flambé ware. schemes could be repeated at will: correct mixtures in glazing combined with certain temperatures and careful timing could be relied upon to produce results which would show little variation. Much higher temperatures were used in the firing of flambé pieces, the precise result in colour could not be foretold, and each left the furnace as a unique and unrepeatable example. The great heat to which they were subjected produced interpenetrating and palpitating colour effects of astonishing range and beauty, and we can well imagine the fascination with which the completion of a firing must have been watched, and the hope perpetually attending it that by some subtle factor due to the mixing of the colours, the heat, the position of the clay in the furnace, or to all three, there would be produced a new masterpiece of undreamt of beauty, worthy to stand alongside the world’s finest examples of ceramic art. Uncertainty may have filled the potter’s mind on such occasions, but it was a glorious uncertainty.

Just as in form there had been no manipulation, no slight pressure or relaxation of the potter’s thumb that had not its meaning, so in colour there was no applica tion, no touch of oxides here or there, no scrupulous regulation of the heat of the furnace or duration of the firing which it was not expected, or hoped, would yield beautiful result. It was an art in which too much thought could not be taken, nor too much care exercised, and if beauty came by chance, it was not until after much diligent labour had been expended to make it so. The wide range of exquisite purples, rose-purples, mauves suffused with crim sons, and ivories with that strange greyish crimson known as pigeon’s blood, above all, the glorious sang de boeuf examples, all are a tribute to Howson Taylor’s unceasing determination to make his clay bloom with a richness or delicacy of colour which could be compared with little if any loss of distinction to the finest achievement of Chinese ceramic art.

The comparison of his work with that of the Ming period—a comparison made early in his career was recalled at the outset of these comments on Ruskin pottery. But I think a more just comparison may be made with some of the best examples of the Sung period. The maker of Ruskin ware was nearer in spirit and in craftsmanship to the masters of the Sung Dynasty than to those of any other period; and as it was they who brought the world’s greatest ceramic art to its most wonderful efflorescence, it is measure of his excellence that he invites comparison with them. He had much of the classic dignity, the breadth and power of form which characterized Sung work, and his colours and glazing, if they were not absolutely the equal of Sung ware, came as near to it as any ceramic art since created.

It becomes indeed a fascinating exercise of one’s aesthetic sense to make a direct comparison between, for example, one of the rich rose-purple pieces of Sung Chün and a similar piece of Ruskin. Taylor followed one of the main tendencies of the Sung period in the preference he showed for monochromes, and again in his insistence upon the use of one dominant colour in polychromatic pieces. The minor, or subordinate, hues in his colour schemes were suffused with the others with hardly less subtlety than that which characterized Sung art, and his sang de boeuf pieces have a brilliance of colour and warm depth of glazing which combine to yield a decorative richness capable of holding its own beside the best Chinese examples. If he did not explore the mysteries of colour quite so deeply as the of tone and surface texture in the celadons, or achieve quite Chinese, or capture so completely their indescribable beauty the same warm life in the glazing which makes the experi ence of looking at a fine Sung example an annihilation the same high category of technical accomplishment, un of space and time, nevertheless he stands with them in equalled in his own day.

It is fairer, I maintain, to compare him with the Sung potters rather than with those of the Ming epoch, not least because Ming ware, though it remained considerably monochromatic, saw the develop ment of decoration to an extent which Howson Taylor never aspired to emulate. It is true that he often applied decoration in hand-painted patterns, or in the form of the clay by slightly raised under-glaze designs, but his restraint in these directions is a marked point of departure from later Ming ware. Purity of the shape, beauty of the colour, and life of the glaze were his absorbing aims. He never ceased experimenting in colour and glazing, continually going to nature for inspiration, deriving it from a wide maidenhair fern against a grey background. To achieve delphinium, perhaps from the colour and form of variety of sources, a leopard’s skin, the particular tone of

some of his most charming effects in suffused colour, he would often give an example more than one firing, till an early colour had been burned away and only the merest hint remained, to fade almost imperceptibly into the new one.

It was experiments such as this which engaged him to the last, and made him yet more eager towards the end of his life than he was at the beginning to win new beauty from his craft; and it was by efforts such as these that he gave to some of his latest examples a surpassing loveliness of colour and surface quality in dappled greys and greens and rich purples and crimsons.

Throughout his career, Howson Taylor’s research in colour and glazing was progressive, and yielded an increasing mastery of his craft, which brought him constantly nearer to the consummate excellence of the ancient Chinese. The abandonment of the local clay in his young days was dictated by the desire for a whiter and purer ‘body’ which would yield greater luminosity in colour. During the early period, his most successful pieces were the translucent greens and blues, especially the lapis lazuli shades. Later, he devoted a great deal of attention to the blood reds and greys, and his grey pieces with a slight blush of red are highly prized by collectors who appreciate the real difficulties of potting.

These in the flambé pieces, which included a very wide range of copper reds and greys and greens, were fired at a temperature of about 1600° centigrade, where control is very limited and minute differences accounted for big changes in colour. For the mingling and gradations of colour, and the intensity of application of the various metal oxides, but upon the quan perature and the chemical composition of the glazes and the colour itself, were dependent not only upon the tem tity of sulphur present in the kiln, and the position of the pieces. Thus, of two pieces of ware, each given a coating of the same glaze and each treated in exactly similar fashion. one might come out pale blue and grey, another blood red and grey. It will be apparent, therefore, with what intense interest the opening of a large kiln, containing perhaps £1,000 worth of ware, would be watched, and how, in the early days, there were many painstaking attempts to decide and record precisely what factors had gone to deter mining the result, so that in future it might be repeated.

In this manner a great amount of knowledge accumulated gradually, and from what was in the first place largely speculative art, the results of which could be foreseen only vaguely, there was developed, by empiric methods, something approaching a scientific degree of control. Yet the possibilities in colour and tone and surface treatment remained inexhaustible: the more certain knowledge be came, the more apparent did it become that mixtures and glazing and temperatures, to mention only the main factors, held many secrets, the discovery of which was the reward of endless patience and intuition. During the last four or five years much attention was devoted at Ruskin Works to the production of crystalline and matt glazed wares, and their maker often spoke with pride of the suc cess which attended his research into the production of these glazes.

The highest technical achievement of the in recapturing something like the Chinese depth and Smethwick potter, however, was beyond question his success in recapturing something like the Chinese depth and brilliance of glazing and colour in the wonderful sang de boeuf. His greys, greens, blues and yellows were distinctive and full of charm, but the sheer joy of colour in the Ruskin sang de boeuf remains one of the glories of modern ceramic art, and it may be predicted confidently that, just as the have been treasured for centuries, losing nothing of the well-nigh priceless examples of the Sung and Ming periods beauty with which they came fresh from the kilns, so these Ruskin examples will be prized for many generations.

The underglaze red was an invention of the Chinese, and has been at all times one of the most difficult of all ceramic colours to control. The softening and deepening of the colour by the high temperature at which the glaze was melted, and its infinite gradations through purples to smoky greys and lavenders, yield the richest artistic results, perhaps the equal, in quality, of the indescribable depth and softness of the Sung celadons. The most refractory of glazes proved only a temptation to Howson Taylor to experiment further, continually searching for true pottery colour, and always insisting on underglaze painting, method vastly differing from on-glaze painting, which in the Ming period opened the way to the decadence of naturalistic realism in decoration. Underglaze painting freedom and fidelity to pottery as an art form which characterized the best Chinese work could be recovered: and this singleness of purpose dominated the whole of his was to him the only method by which the richness and artistic life.

Though a man of such humility and modesty when it came to discussing his work in terms of commercial value, Howson Taylor by no means underestimated the worth of his finer pieces, a fact which may be judged from the knowledge that he insured one for £850.

In the matter of marking his ware, he was so wayward that the determination of a chronological table of marks seems well-nigh impossible. The earliest ware was known as Taylor pottery, and the first mark used apart from the name was a rough approximation of a pair of scissors treated in the same way as the old Dresden mark of the crossed swords. During this early period the ware was also identified by the initial letters of his name in the form of monogram. The name of Taylor was dropped when the early international successes were achieved. At that time Ruskin’s influence upon the arts and crafts of England was at its height, and both Edward Richard and Howson Taylor were earnest disciples of his gospel of honesty in art of all kinds. Ruskin’s permission to use his name on the pottery was sought, and it was used as early as 1904. Not for some years, however, was the registering of the name Ruskin pottery considered, and the letter from Mrs.Severn which made this possible is appended, together with a list of the marks used.

In 1926 Howson Taylor presented to the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, in memory of his father, an excellent collection of his work, in which are to be seen some of the most beautiful sang de boeuf specimens. The South Kensington Museum, the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, the Leeds, Nottingham, and Stoke-on-Trent Galleries have notable collections, and many important galleries throughout the world possess examples. It was character istic of Mr. Taylor that he presented, shortly before his retirement, a collection to the Public Library at Smeth wick. It includes several examples brought from the kilns in the last year of his activity as a potter, when he was thinking of his retirement. True to the undertaking it has been understood he gave to his father not to sell what knowledge he could impart, he declined several offers for the acquisition of the factory, and with his departure from had been in one man’s lifetime a substantial pageant, in Smethwick the production of Ruskin pottery ceased. It which beauty succeeded beauty and ceramic art experienced once more a rebirth of the technical mastery and pure aesthetic sense of old. Artistic passion sustained all he did, and if the making of Ruskin pottery enjoyed only a brief glory in years, its examples remain, to be treasured, beyond doubt, for centuries.

The letter from Mrs. Severn giving Howson Taylor permission to use the name of Ruskin is as follows:

Brantwood, Coniston Lake, 6th August, 1909.

‘Dear Sir, We got back from the opening of the Ruskin Exhibition at

Keswick yesterday evening too late to catch post or even to unpack until this morning the pottery you have so kindly sent, as specimens of your work. It has greatly interested my husband and myself and we think it more than kind that you should wish us to accept as a gift, the specimens—some of which we greatly admire, and feel sure Mr. Ruskin himself would also especially those with the beautiful opalescent colouring and the more joyous blues, greens and golds, rather than the dull, sombre deep reds and browns. There is an exquisite green bowl that every colour goes well with. We have tried red currants, grapes, etc., and they all look lovely on it, and there is a vase of the same into which I have put my best roses, pink and deep red. It now stands in Ruskin’s study in front of his portrait, and I feel we can now, gladly, give you permission to patent his name for your pottery. green leaves round are very lovely and delicate and so The opalescent golden yellow bowls with wreath of light to hold in the hand. The coppery one, though so rich, looks almost as if it were metal. The turquoise candle-sticks are charming and stand solidly, though having no rim, will need glasses and I am not sure whether the little saucer is to hold the thing of same hue as our egg-cup, or extinguisher.

The deep lapis lazuli blue is very fine-though I almost wish the inner side of the wretched little bowl were blue also, instead of purple. Then even on the dark ones there is a wonderful bloom, almost like that on a ripe plum. The greyish vase is not so interesting in colour—though useful in form—but it is delightful the variety and unexpected colouring that comes in varied light. Please kindly send us your coloured illustration’ circular, that we may show it here to friends who may wish to get some.

Believe me, dear Sir, faithfully yours,

(Signed) Joan Ruskin Severn.

We were friends of his granddaughter we have one of his pots.